Vedic Worship

There is no indication of temples in the Vedic period. Also, there is no record of idol worship in the Vedas. However, there is mention of altars. The altar (vedi) was considered to be earth’s extremest limit; and sacrifice, the navel of the world (RV.1.164.35). One of the altars was made to sit on the earth, was considered to be eye-shaped, and the sacrifice was directed sun-ward. Trimmed ladle was used to pour oil into the altar’s fire (RV.6.11.5). However, there were altars of various other shapes as well.

B.G. Sidharth suggests a possible “connection between the fire altars in Turkmenistan (Togolok) and Afghanistan (Dashly) and the Harappan civilization, particularly Kalibangan, where there are seven fire altars, and also with the Harappan seal showing worship at a fire altar with seven accompanying deities.”[1] He tries to reconcile these archaeological discoveries with the concept of the seven fires in the Rig Veda which he considers to be purely astronomical and connected with the myth of the Pleiades or Krittika and the seven stars of the Great Bear or Sapta Rishi (the Seven Sages).

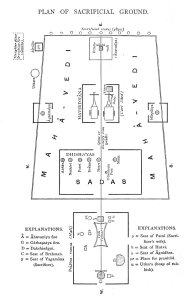

For the Vedic priests, the altar was not just a random structure; it had cosmic relationship—it was earth’s extremest limit, the sacrifice was the center of the world. Meticulous calculations were made to assure the positioning of it. Astronomical, geometrical, and mathematical calculations came into play when situating and constructing an altar. Some have suggested intricate astronomical relations in the choice of the number of stones and pebbles to be placed around the altar.[2] The A.B. Keith notes that the altar was arranged to represent earth, atmosphere, and heaven, and the same arrangement is devised in the fire-pan.[3] There were elaborate procedures of determining the shape and size of altars, setting up of fire; various kinds of sacrifices and offerings; timings for setting up the altars and performing the sacrifices, etc. For instance, the Garhapatya altar was round whereas the Ahavaniya altar was square. There were new moon and full moon sacrifices, four-month or seasonal sacrifices, first-fruit sacrifice, pravargya or hot milk sacrifice, and animal sacrifice.[4] One important sacrifice was the Soma sacrifice in which animals like goats and cows were sacrificed to various deities.[5]

The chief priest was Agni (Fire). Since Fire is kindled by mortals and assumes an immortal nature, it is considered to be the mediator between mortals and immortals; it carries the sacrifices to the gods and draws the gods to men (RV.1.1.1-3). Agni is considered the sapient-minded priest (1.1.5), the dispeller of the night (1.1.7), the ruler of sacrifices, guard of Law eternal, and the radiant one (1.1.8). Therefore, utmost care was taken in kindling the sacrificial fire.

[1] B.G. Sidharth, The Celestial Key to the Vedas: Discovering the Origins of the World's Oldest Civilization (Vermont: Inner Traditions, 1999), p.101

[2] M. I. Mikhailov, N. S. Mikhailov, Key to the Vedas (Minsk: Belarusian Information Center, 2005), p.201

[3] A.B. Keith, The Religion and Philosophy of the Veda and Upanishads (New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1925), p.466

[4] Ibid, pp.313-335

[5] Ibid, pp. 326-332

B.G. Sidharth suggests a possible “connection between the fire altars in Turkmenistan (Togolok) and Afghanistan (Dashly) and the Harappan civilization, particularly Kalibangan, where there are seven fire altars, and also with the Harappan seal showing worship at a fire altar with seven accompanying deities.”[1] He tries to reconcile these archaeological discoveries with the concept of the seven fires in the Rig Veda which he considers to be purely astronomical and connected with the myth of the Pleiades or Krittika and the seven stars of the Great Bear or Sapta Rishi (the Seven Sages).

For the Vedic priests, the altar was not just a random structure; it had cosmic relationship—it was earth’s extremest limit, the sacrifice was the center of the world. Meticulous calculations were made to assure the positioning of it. Astronomical, geometrical, and mathematical calculations came into play when situating and constructing an altar. Some have suggested intricate astronomical relations in the choice of the number of stones and pebbles to be placed around the altar.[2] The A.B. Keith notes that the altar was arranged to represent earth, atmosphere, and heaven, and the same arrangement is devised in the fire-pan.[3] There were elaborate procedures of determining the shape and size of altars, setting up of fire; various kinds of sacrifices and offerings; timings for setting up the altars and performing the sacrifices, etc. For instance, the Garhapatya altar was round whereas the Ahavaniya altar was square. There were new moon and full moon sacrifices, four-month or seasonal sacrifices, first-fruit sacrifice, pravargya or hot milk sacrifice, and animal sacrifice.[4] One important sacrifice was the Soma sacrifice in which animals like goats and cows were sacrificed to various deities.[5]

The chief priest was Agni (Fire). Since Fire is kindled by mortals and assumes an immortal nature, it is considered to be the mediator between mortals and immortals; it carries the sacrifices to the gods and draws the gods to men (RV.1.1.1-3). Agni is considered the sapient-minded priest (1.1.5), the dispeller of the night (1.1.7), the ruler of sacrifices, guard of Law eternal, and the radiant one (1.1.8). Therefore, utmost care was taken in kindling the sacrificial fire.

Shatapatha Brahmana

The Shatapatha Brahmana, a part of the White Yajur Veda, dated between 700 BC and 300 BC, elaborates details of the various rituals used in Vedic worship. The name Shatapatha means “hundred paths”. The Brahmana contains portions that may have been orally transmitted through generations before committed to writing about 300 B.C. It is a valuable source of information regarding the thought and life of the Vedic people. Some notable points are as follows:- The gods and Asuras sprung from Prajapati and were both soulless mortals until the gods decided to place the immortal element of fire (Agni) within themselves, thereby becoming immortal (2.2.2.8-14).

- The term Upavas for “fasting” is given a rationale. Upa means "near" and vas means "abide" or "dwell". It is stated that on the day of fasting (upavas), the gods betake themselves to the house of the sacrificer, who would be offering sacrifices of food for the gods to eat. Therefore the day is called upavasatha (or the day of fasting). The rationale behind this fasting is that it is improper for the host to eat before the guests, staying in his house, have eaten; "how much more would it be so, if he were to take food before the gods (who are staying with him) have eaten: let him therefore take no food at all." (1.1.1.7-8). However, the sacrificer is permitted to eat plants and fruits from the forest since there is no offering made of things from the forest, and “that of which no offering is made, even though it is eaten, is considered as not eaten.” (1.1.1.9).

- Brahman is a general name for priests, and there were brahmans also among the Asuras (1.1.4.14).

- The food of the gods is amrita (ambrosia, or not dead), for they are immortals; therefore, rice must be grinded (killed), and then bestowed with immortal life before offering to the gods. Sacrifice, thus, involves the concept of death and immortality (1.2.1.19-22).

- In a sacrifice, the animal or grain being offered dies; however, by giving dakshina to the priest, one invigorates the offering, making it successful (2.2.2.1-3).

- Anyone who makes an offering without giving dakshina (gift to the officiating priest) gets sins wiped off on self (1.2.3.4).

- Rice and barley are ordained as the five-fold animal sacrifice for two reasons: (a) the gods first offered a man as the sacrifice, but the sacrificial essence left him and entered a horse; they offered the horse, the essence left the horse and entered the ox; they offered the ox, but the essence left it and entered the sheep; they offered the sheep, but the essence left it and entered the goat; they offered the goat, but the essence left it and entered the earth; so, they digged in the earth and found it in the form of rice and barley (1.2.3.6-7). (b) The rice-cake, as rice-meal is the hair; when water is poured on it, it becomes skin; when mixed, it becomes flesh; when baked, it becomes hard as bone; and when taken off the fire and sprinkled with butter, it changes into marrow. "This is the completeness which they call 'the fivefold animal sacrifice.' (1.2.3.8).

- Ghee or clarified butter is an important part of the sacrificial rite; it is likened to a thunderbolt (3.3.1.3).

- The sacrifice is the representation of the sacrificer himself (1.3.2.1).

- The altar is compared to a woman of honor who must be clothed in the presence of gods and priests. The altar represents the earth, and the barhi grass with which it is covered represents the plants fixed firmly on the earth (1.3.3.8-10).

- Only Brahmans, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas were considered able to sacrifice (3.1.1.9).

- The housewife (patni) participates in the sacrificial rite (1.2.5.21; 3.4.1.6).

- The one who wishes to perform the rite of consecration must shave his hair and beard and cut his nails because that part of the body where water does not reach is considered impure (3.1.2.2).

- Elaborate measurements are given for the construction of the altars, with rationale for each measurement in the Brahmana.

- Breath is declared to be the one God, of whom the myriads are just powers, proceeding first as one and half Wind, then the three world where all gods dwelt, and then into thirty three, and three hundred and three and three thousand and three (11.6.3.10).

- The world of the fathers is differentiated from the world of the gods (1.9.3.2). The sacrifice aims to go to the world of gods (1.9.3.1).

[1] B.G. Sidharth, The Celestial Key to the Vedas: Discovering the Origins of the World's Oldest Civilization (Vermont: Inner Traditions, 1999), p.101

[2] M. I. Mikhailov, N. S. Mikhailov, Key to the Vedas (Minsk: Belarusian Information Center, 2005), p.201

[3] A.B. Keith, The Religion and Philosophy of the Veda and Upanishads (New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1925), p.466

[4] Ibid, pp.313-335

[5] Ibid, pp. 326-332

Comments

Post a Comment